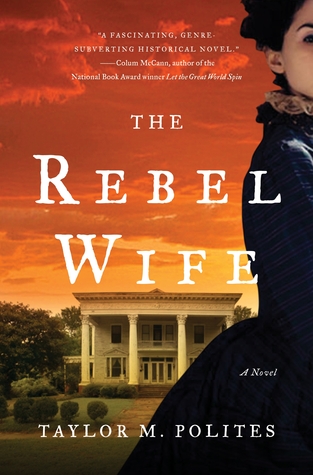

The Rebel Wife Book Summary-Set in Reconstruction Alabama, Augusta “Gus” Branson’s is a young widow whose quest for freedom turns into a race for her life when her husband Eli dies of a swift and horrifying fever and a large package of money – her only inheritance and means of survival – goes missing. Gus begins to wake to the realities that surround her: the social stigma her marriage has stained her with, what her husband did to earn his fortune, the shifting and very dangerous political and social landscape that is being destroyed by violence between the Klan and the Freeman’s Bureau, and the deadly fever that is spreading like wildfire. Nothing is as she believed, everyone she trusts is hiding something from her.

The Rebel Wife is set in late Spring 1875, after the November 1874 elections in Alabama brought the Democrats back to power and restored what many refer to as “home-rule.” This was the end of Reconstruction, close to ten years after the end of the Civil War. When I was growing up in Alabama and learning about the period, the big event was the Civil War. Very little was said about Reconstruction other than it was a terrible time of much suffering under some sort of forced and corrupt Republican rule. All the books and movies seemed to focus on the dramatic events of the war (as they still do), neglecting its coda, a period twice as long as the war itself in which dramatic and often futile efforts were made to fundamentally change the way Southern society was organized—economically, socially and politically. The cornerstone of this process was the enfranchisement of African-American men, the vast majority former slaves. Legislators in the federal capital believed that arms would not be available forever to enforce the civil rights of the recently freed people, but the vote would serve as their protection—that is, their participation in self-government would ensure that they would have a voice at the ballot box to influence government. The Civil Rights Act of 1875, passed February 1875, offered further federal guarantees of civil rights, regardless of race. By 1883, however, the act was struck down by the Supreme Court in a series of cases that denied that the federal government could intervene in the states over civil rights issues—States Rights won this round, each state being granted exclusive authority over the regulation of the rights of their citizens. The legislative drama ultimately put to bed by the Supreme Court was also being played out in the broader culture that reflected the growing national fatigue with the struggle over black civil rights and desired a consensus of white national unity over race politics. In the process of post-war national reconciliation, the Reconstruction program of equality (that was truly radical for the time) became the casualty.

The period of Reconstruction contained as much drama as the Civil War, but has remained a step-child to the main event of white America’s war with itself. As the debate over the extent of Federal power over the states, which one would think would have been concluded in 1865, continues, so does the debate over the extent and meaning of the “Civil War amendments”, the 13th, 14th and 15th, which abolished slavery, ensured citizenship for American-born people regardless of race, and guaranteed the right of all American citizens to vote. These political changes were made against the backdrop of economic collapse and racial violence that consumed the South in the years after the war, a fertile and rarely turned ground for a dramatic narrative. The rare cultural discussion of Reconstruction drew me to the period. But when we look back at the war (especially now in the midst of its 150th anniversary), we cannot understand what the war was about and what changes it made without thinking about, asking about Reconstruction. The Rebel Wife, I hope, opens a door to that discussion for readers who have that interest. I want it first and foremost to be a fascinating read, but I also want to add another layer to the exchange between literature and history, to the often blurred lines between fiction and reality.-Taylor

Taylor M. Polites is a novelist living in Providence, Rhode Island with his small Chihuahua, Clovis. Polites’ first novel, The Rebel Wife, is due out in February 2012 from Simon & Schuster. He graduated in June 2010 with his MFA in Creative Writing from Wilkes University. He has lived in Provincetown, Massachusetts, New York City, St. Louis and the Deep South. He graduated from Washington University in St. Louis with a BA in History and French and spent a year studying in Caen, France. He has covered arts and news for a variety of local newspapers and magazines, including the Cape Codder, InNewsWeekly, Bird’s Eye View (the in-flight magazine of CapeAir), artscope Magazine and Provincetown Arts Magazine.

I want to thank Taylor for stopping by today!

I find this time period fascinating and look forward to reading The Rebel Wife!